Højgaard-Smitshuysen pioneering invention

DynElectro’s research has made it possible to store wind energy better and cheaper. And it can boost the green transition. Media darling Anne Lyck Smitshuysen explains how we did it.

Time was running out for Anne Lyck Smitshuysen.

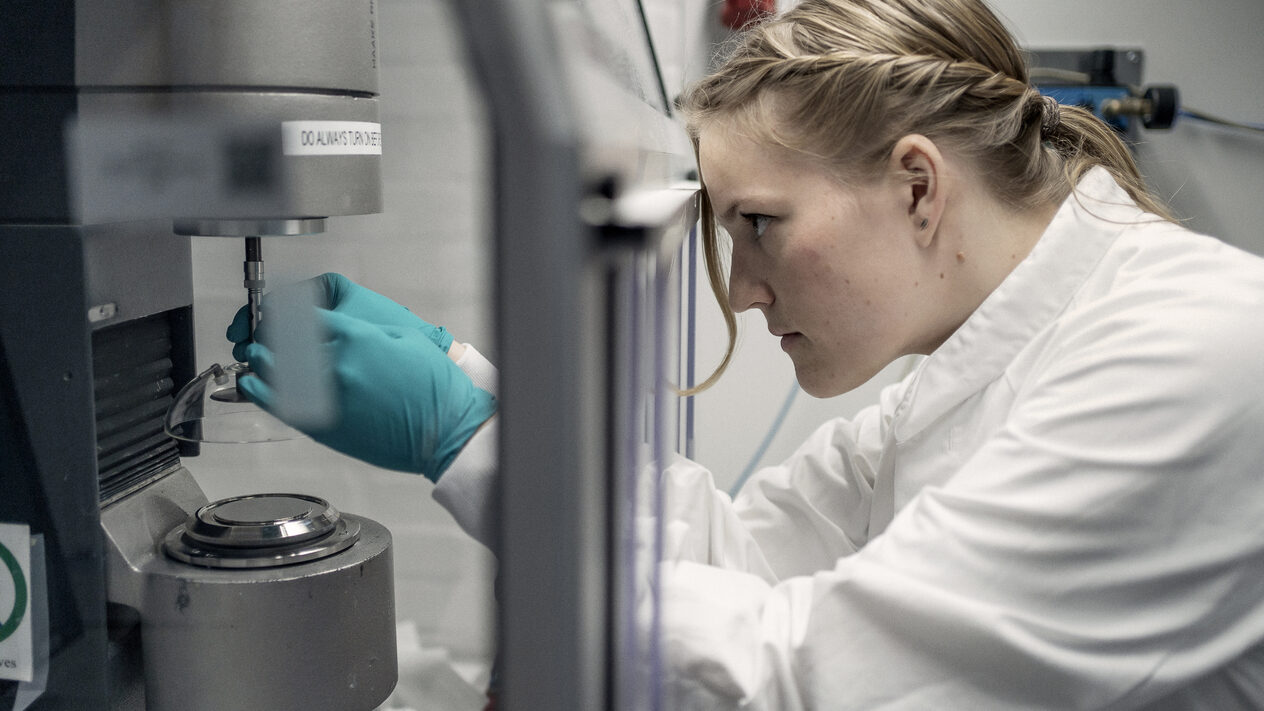

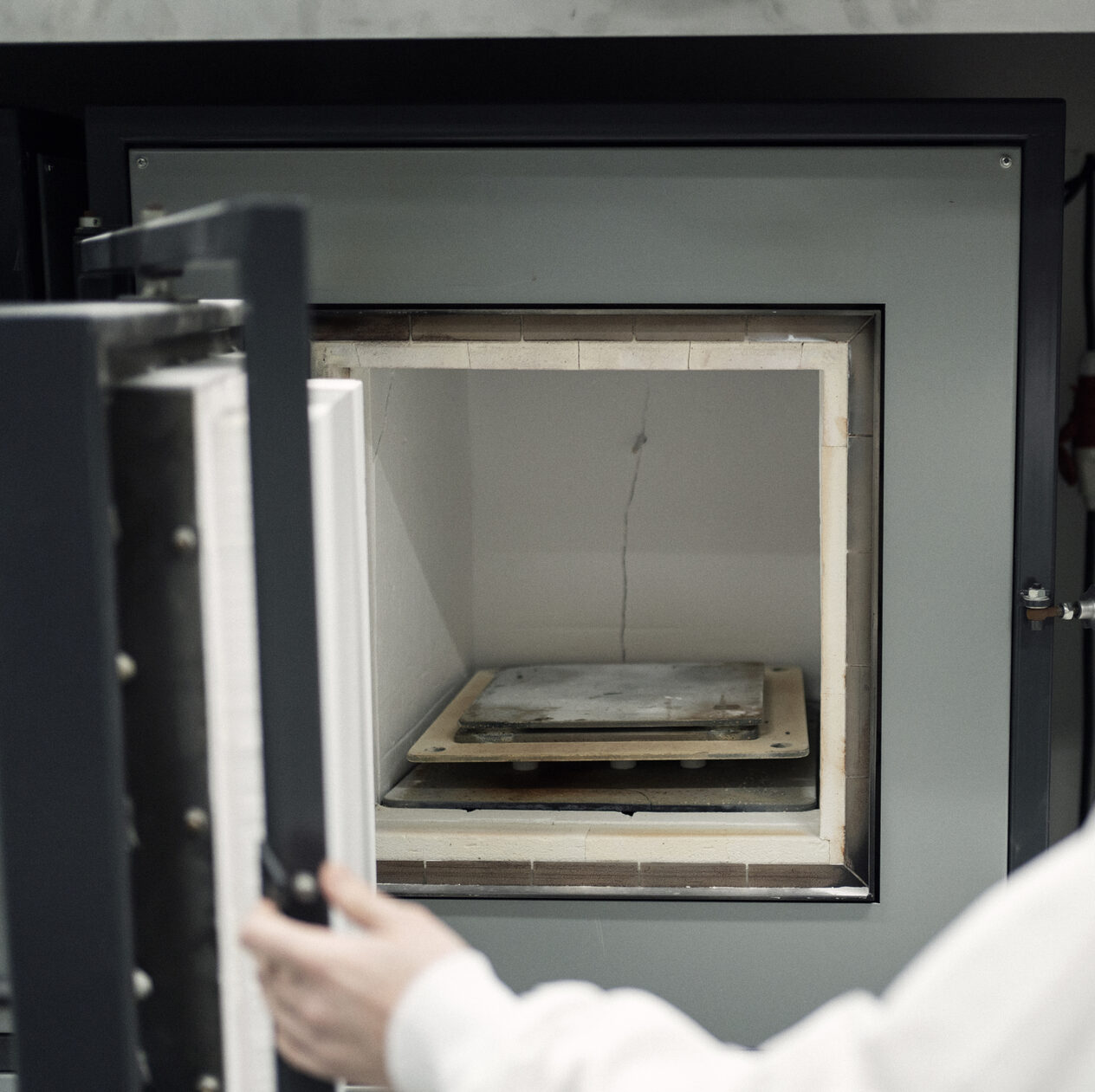

The 27-year-old physics student was three weeks before submitting his thesis after having “lived at DTU for months”. And she still hadn’t made the breakthrough she was chasing. Then, in February 2021, she opened a furnace in the lab to see the result, she was struck by an adrenaline rush.

My first thought was: “Wow!” I was surprised and excited and had to share the experience with someone,” she said. She immediately took a picture of the contents, which she sent to Søren Højgaard Jensen (her supervisor and co-patent inventor), who also could not believe his own eyes.

It was big.

Anne Lyck Smitshuysen says that she grew up in a home where it was natural to save electricity and sort her waste.

This has made sustainability a big part of her life.

The invention that came out of the furnace a year ago can speed up the green transition. It has secured Anne and Søren’s status as a star scientists, recognition and awards both at home and abroad. And it’s a testament to a very special work ethic.

Can store green energy

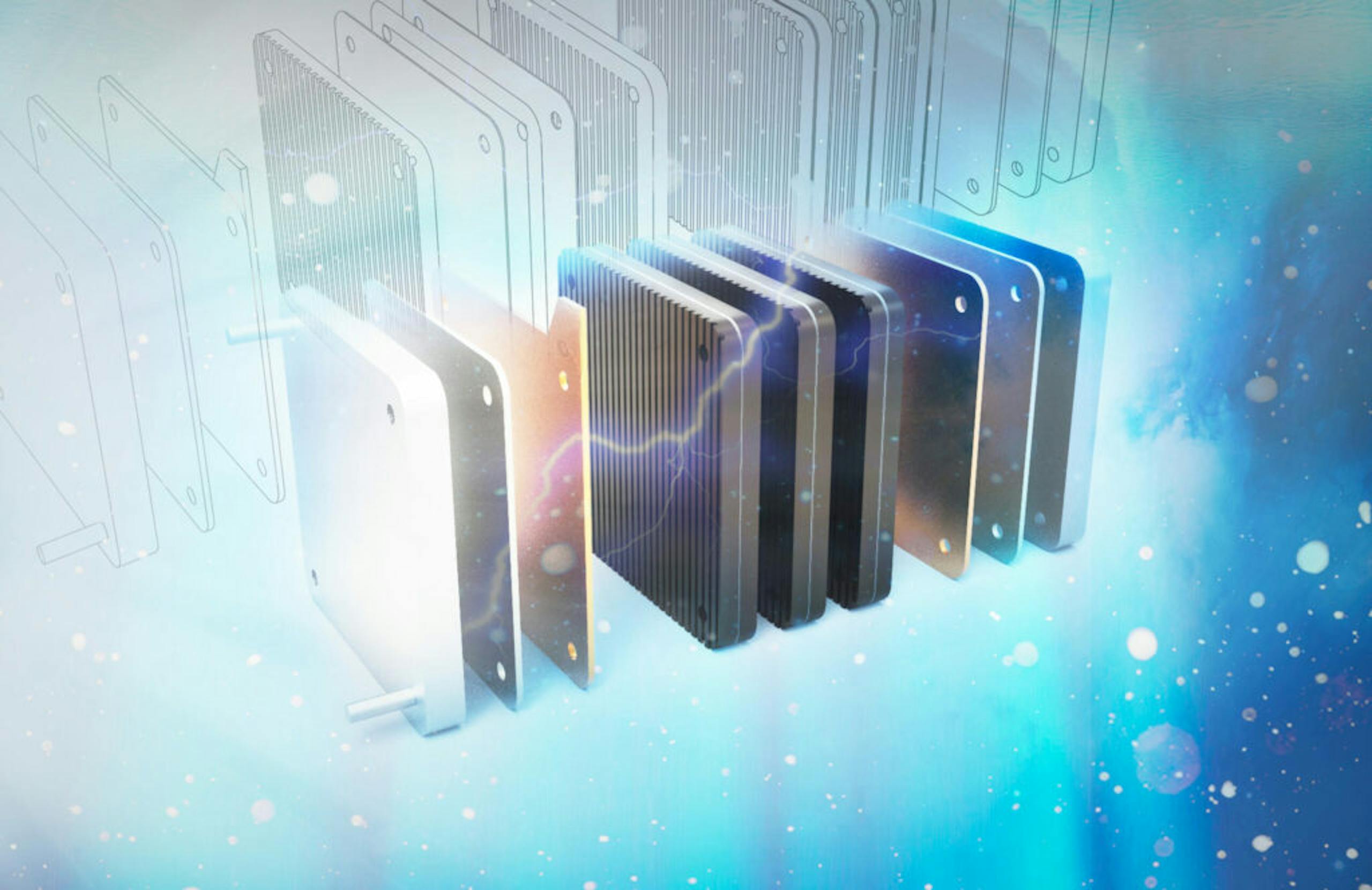

The technology that Anne Lyck Smitshuysen works with is called electrolysis cells and is predicted to play a role in making Denmark and Europe independent of fossil fuels. “I think I’ve always had an idea that I want to make a difference in how we use our energy,” she said.

About Anne Lyck Smitshysen

Anne Lyck Smitshuysen is 28.

She was born and raised in the town of Sjølund near Kolding. Today she lives in Birkerød with her husband and daughter of three years.

She studied physics and nanotechnology at the Technical University of Denmark and completed her master’s degree in 2021.

Is now in the process of a business PhD at the Power-to-X company DynElectro and the Technical University of Denmark. The company is a startup with Karsten Klemens Hansen, Søren Højgaard Jensen (both supervisors on the project) and Samantha Jane Philips at the forefront. Her university supervisors are Bhaskar Reddy Sudireddy and Henrik Lund Frandsen.

Specifically, she has done this by further developing the electrolysis cells so that we can get much more out of the green energy we produce.

For the now 28-year-old researcher, interest in physics and chemistry sprouted already in high school.

Here she first became acquainted with how the chemical process electrolysis can “store energy”. And this can be used to make even better use of wind power, for example. If we do not use the power produced in the Danish wind turbines – such as at night, when the power demand is small – it is practically lost.

It is fantastic that more wind farms are being built, but when we do not have a way to store the power, extremely many have to be built before we start to cover our energy needs in the daytime, explains Anne Lyck Smitshuysen.

There are already technological possibilities for storing energy, but it is expensive to manufacture and therefore cannot yet compete with oil and gas. And this is where the young researcher’s invention and the furnace at DTU come into the picture.

Innovation and technology

The electrolysis cell developed by Anne Lyck Smitshuysen also has the ability to store energy. It’s just way bigger, which can bring down production costs by 50 percent.

The best part is that others can suddenly see the coolness in what I – and many others – have been geeking out about for years.

“Doing something bigger” might sound simple. But make no mistake. Scientists around the world have spent years solving the problem. So it has required out-of-the-box thinking and a “great deal of persistence,” as Anne Lyck Smitshuysen says.

The idea already began to form during her maternity leave because it tingled so much in her to use her engineering brain again.

Why hadn’t anyone succeeded in making these electrolysis cells bigger? Anne Lyck Smitshuysen wondered. She immediately started creating 3D models on her computer, and she tweaked the theories.

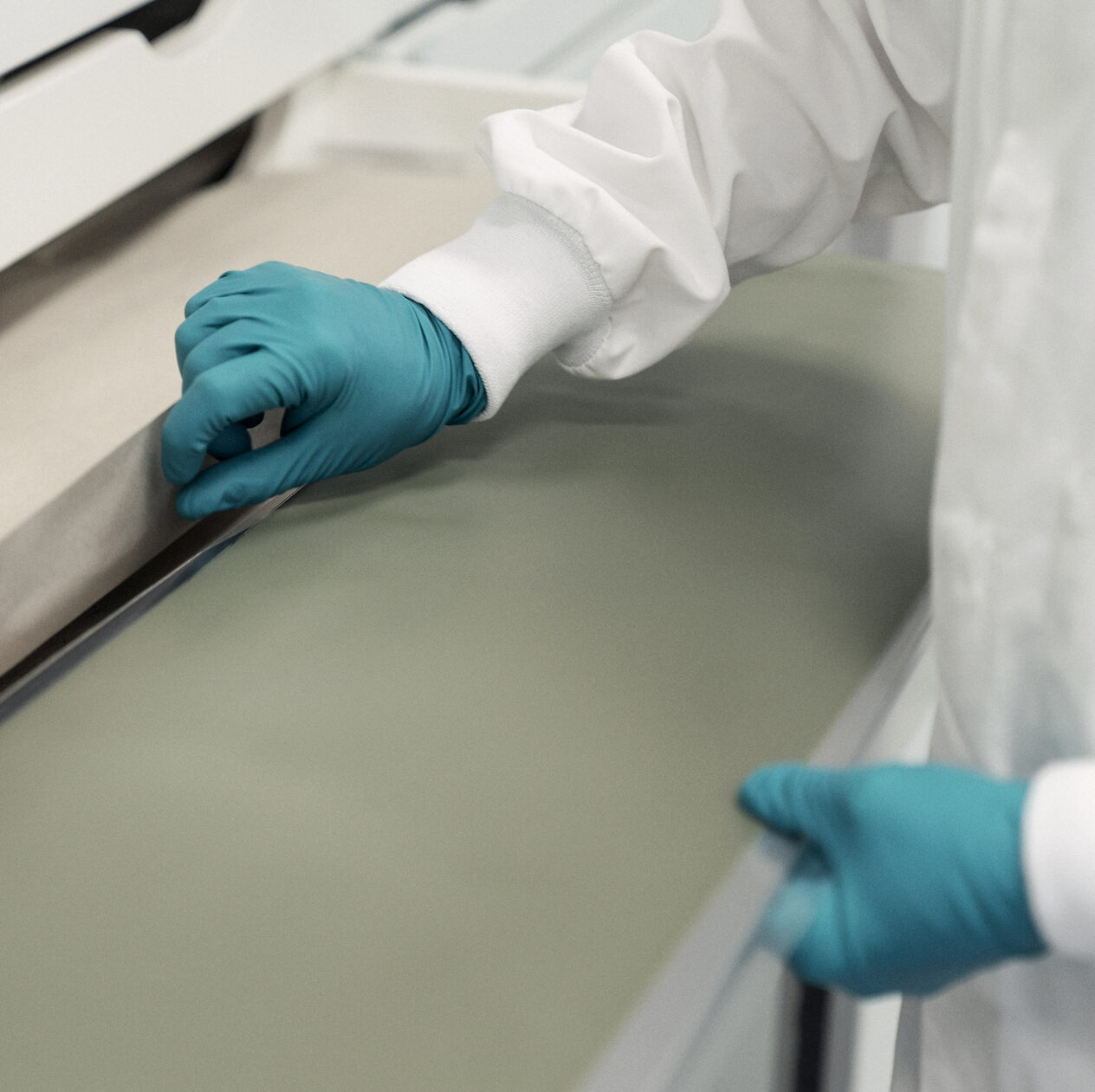

In the lab, she fabricated the electrolysis cells in the hope that after their burning they would come out as they should — like half a millimeter thick porcelain-like squares.

Over 75 times, she opened the oven and saw that the cells had crumpled or destroyed. So with less than a month to go until the deadline, she began to doubt whether it would even succeed.

A special work ethic

It is a matter of keeping going, even if it does not go exactly as you hope, says Anne Lyck Smitshuysen. “It was hugely demotivating that over and over again it didn’t work, but I’m also pretty stubborn. When I get an assignment, I don’t give up until it works. Or someone else says that now I have tried enough,” she says and laughs.

And that was good. Because it was here – a few weeks before the delivery – that she opened the oven and saw something new.

Inside was a completely intact cell the size of a computer screen – that is, over six times larger than the original ones, which are the size of a slice of bread. I called my supervisor pretty quickly and said: “Søren, I have sent you a picture you need to see. Now,” says Anne Lyck Smitshuysen.

Søren was also excited. Their success was an international breakthrough.

In research, that one incredible result is not enough, and it takes a lot of trying before you can say that something “works.”

In the Højgaard-Smitshuysen method, which Anne further develops, she has added an “extra unique step” before the burning, however, has long since been stamped. The step I’ve added makes them not curl up. That way we can increase the size, she says.

A new everyday life

Today, the invention is still a huge part of Anne Lyck Smitshuysen’s everyday life.

She has chosen to continue her research into an industrial PhD. with DTU and in the company DynElectro, which is working to get the technology from the laboratory into production.

“Right now, we’re optimizing everything. We have the building blocks, and then the corners just need to be filed so we can have a nice house,” she says.

Where they are currently seven full-time employees in the company – among others her former supervisor Søren Højgaard Hansen – they expect to face a growth adventure thanks to Anne and Søren’s research. Looking at a larger perspective, there are even wilder prospects.

Has cut 15 years off the EU’s target

The transition to sustainable forms of energy will be much faster. In addition to storing wind energy, electrolysis cells also form hydrogen, which can be used as fuel for trucks and trains, among other things.

The European Commission has a target of hydrogen covering 24 percent of energy needs. That goal is likely to be achieved as early as 2035 with the Højgaard-Smitshuysen invention – that is 15 years before the goal.

For Anne Lyck Smitshuysen, it can still feel unreal that she is the one who helped crack the code. A code that scientists around the world have been working on for years.

“You get a little humbled when journalists and people from abroad suddenly take an interest in you. It’s crazy to be part of making a green future. But the best part is that others can suddenly see the cool in what I – and many others – have been geeking out with for years,” she says and laughs.

Anne has most recently been named one of the 100 greatest business talents in 2021 by Danish newspaper, Berlingske, she has received the prestigious Flemming Bligaard Prize of DKK 500,000 from the Ramboll Foundation for her research, and recently she has been nominated as Future Hydrogen Leader by the international Sustainable Energy Council.

“We are moving in the right direction when it comes to sustainable alternatives. Right now, things are moving fast,” she says.

The original article was written by Silvie Ulrikke Østebø of Denmark’s TV2.

https://nyheder.tv2.dk/2022-04-30-28-aarig-forsker-hyldes-for-sin-opfindelse-troede-naermest-ikke-sine-egne-oejne